Is it time for credit unions to change the lens on how to helpserve the underserved?

|For Dan Emery, former marketing specialist at the $346 millionMaine State Credit Union in Augusta, the answer is yes, whynot?

|“I think credit unions have tremendous opportunities andpotential available to them by getting involved with projects likecommunity gardens, school gardens or helping to promote CommunitySupported Agriculture programs,” he said.

|

Good thing Emery (right) and Chung loaded up on warm gear,since they started their journey in Connecticut on Jan. 8.

|Citing Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, Emery added that while moneyand its related services falls within the second level of safety,food is at the base of the pyramid.

|“If we are trying to improve the quality of life in ourcommunities, build our membership, secure their financial health,and serve those underserved, we can do all of these things byhelping people secure their basic needs,” said Emery.

|“We will not only increase the quality of life for those withinour community, but we’ve now opened our doors to an entirely newmembership base.

|“By showing them that we are more than a financial institutionand by showing them that we want their business because it means wecan help make improvements that directly affect them and theirfamily, this is how we begin to build loyalty.”

|His belief that no one should go hungry and everyone should haveaccess to fresh healthy food is so strong, that in 2012, he foundedthe American Community Project, as a way to raise awareness andfunds for agriculture-based hunger solutions.

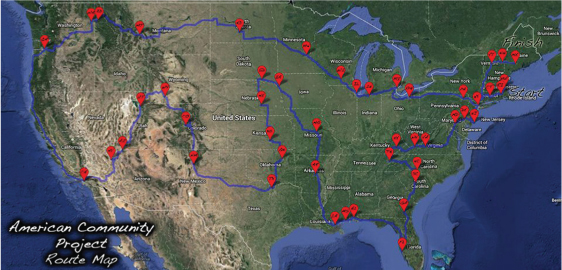

|This year, Emery and a friend, Myles Chung, have taken the ACPon the road. The duo will be exploring local community projectsaddressing hunger needs in 48 states for 48 weeks on mopeds. Thegoal? Simply to gather ideas, raise awareness and $1 million to besplit among the organizations visited.

|Emery said this could include school and community gardens,urban farms, seed initiatives, waste reduction or distributionprojects, or other community projects that help bring fresh,healthy fruits and vegetables to those who need it most.

|The ties of hunger and poverty to homelessness have fascinatedEmery since a trip to Paraguay in 2003. Every day for two monthshe’d see children as young as 5 at busy intersections begging,offering to wash car windows or selling miscellaneous items for afew coins.

|One night on the way he gave a box of pizza to some childrenhanging around a store. His friend explained that while theintention was good, it actually put a target on the kids, who mightwell be beat up for the food.

|“That shocked me. I never experienced anything like that beforeand it made me question the impact and solution of just givingsomeone food,” said Emery. “Was that really the best way to helppeople who are hungry?”

|His search for the answer continued for the next 10 years. In2006, he joined the Maine State CU social responsibility committee,which focused primarily on ending hunger and in 2011, he served onthe Augusta City Council.

|

This map shows the American Community Project route across48 states in 48 weeks.

|During his two and a half years on the council he witnessed howeducation, crime, poverty, hunger, mental and physical health, theeconomy and quality of life together and affected thecommunity.

|Since 1990, credit unions in Maine have invested some $5.3million into ending hunger initiatives. Yet, over the past fiveyears food insecurity has grown from 12% of households to 15%.Emery wanted to get to the root of the issue while uncovering waysto make a positive, long-lasting change.

|“The key questions we’re asking are: What are the challenges?What is being done to solve these problems? What are the mostefficient and effective solutions? Can they be shared with orimplemented within other communities,” said Emery. He said he gotthe hunger tour idea after what would turn out to be his last visitwith his godmother, who’d been battling pancreatic cancer.

|“I was thinking about life and all those things you tend toreflect upon in this kind of situation, and I decided I wanted todo something different. I enjoyed my work, but I wanted to do more.Once the inspiration hit, the brainstorming and planningbegan.”

|

Emery and Chung and their Honda Ruckus scooters hit theroad.

|With his City Council term up in December 2013, he had 22 monthsto save, plan and raise funds for the experience of a lifetime.Maine State CU provided a $5,000 donation to help launch theproject and allowed Emery to post information and promote itthrough its Facebook page and website.

|The duo typically spends three to six days in each location andon travel days average about 80 to 150 miles on their Honda Ruckusscooters. As temperatures finally warm up, they plan to cover200-250 miles a day. They stay on back and state roads as a way toget more familiar with the communities they travel through.

|“We wanted a non-typical cross country vehicle that's great ongas mileage,” said Emery of the scooters. “Besides they are a lotof fun to ride.”

|Emery and Chung stay with friends, family, Rotary Club contactsor those in the CouchSurfing network. They also have a tent fornights lodging can't be found.

|Having only raised $16,000 of the $30,000 budgeted for travel,meant Emery and Chung while exploring hunger and food insecuritywould be experiencing food insecurity themselves.

|“The mental aspect of this trip has been the most difficult,”Emery said. “The lack of security relating to our food and housingis almost always on our minds and the weather has been pretty roughat times.”

|The first day it was 11 below zero and most of their travel daysso far have been in freezing temperatures or in the 30s. As for thefundraising portion of their project, so far $25,000 has beenraised.

|“Now that we are getting more comfortable with logistics andoperating within our nomadic circumstances, fundraising is movingup on our action list,” said Emery. “When it comes to those who arelooking for food there are consistencies in what they want, andit's quite simple. Most people just want an opportunity. If theycan find a way to contribute and make a living for themselves,that's all they’re asking.”

|He added that credit unions, local farms and CSAs have much incommon. Whether it's providing greenhouse loans, farm stand andsmall farm loans, or planting a garden on their property to helpbenefit staffers, a food bank or local school, the possibilitiesfor credit unions to help beat hunger are unlimited.

|“If we think about our place in the financial industry, we existfor more than just the products we supply. We exist because of ourcommunity, and to serve and help strengthen our community. We playa very important role in the success or failure of our localeconomies and in our community's quality of life,” said Emery.

|“Unemployment is nothing more than the state of temporaryjob-related irrelevance. By helping people identify and enhancetheir skills and abilities, we can help them find their relevance,get a job, find a career or start a business,” he said

|“Building community, collaborating, working together for commongoals – this is how we do it. It may seem difficult at first, but Ithink that once we figure it out it will be easier and morerewarding than anyone could have imagined.”

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to CUTimes.com, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited CUTimes.com content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical CUTimes.com information including comprehensive product and service provider listings via the Marketplace Directory, CU Careers, resources from industry leaders, webcasts, and breaking news, analysis and more with our informative Newsletters.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM and CU Times events.

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including Law.com and GlobeSt.com.

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.